By Paul Kupperberg

|

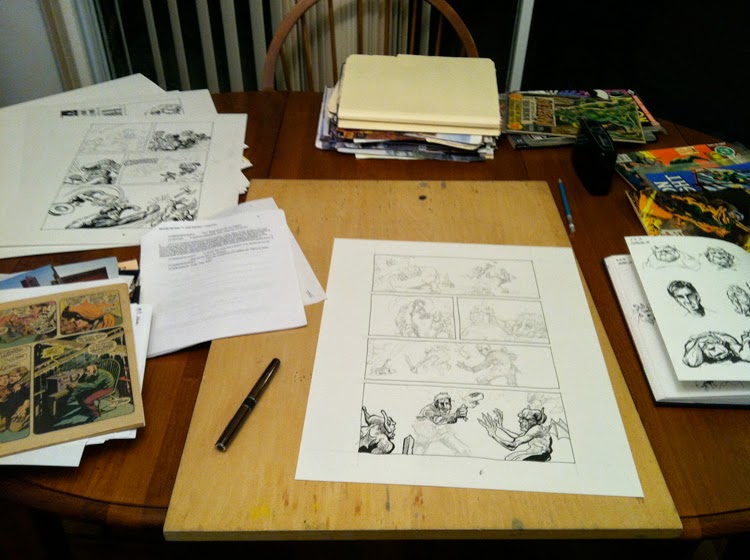

| Portrait of the artist's workspace while drawing "Digger" Graves |

Ideas are a dime a dozen.

I get ideas for stories,

characters, scenes, bits, whatever, all day long. I get them while I’m working

on other projects, while I’m driving, while I’m making dinner, while I’m watching

TV, while I’m in the shower. My mind is always working, always processing my

thoughts in that mysterious way that turns random electrical pulses in the

brain into a story or a creative concept. I couldn’t shut it off even if I

wanted, which, of course, I don’t. Ideas are my job, my bread and butter.

I have probably twenty or

thirty of them a day...although, truthfully, most of them turn out not to be

very good . Execution of a good idea

is hard enough; execution of a bad one is downright painful. The young,

inexperienced writer thinks all their ideas are gold; the experienced ones, in

the words of Kenny Rogers, “knows when to hold ‘em and knows when to fold ‘em.”

With about a thousand comic

book stories under my belt and almost two decades behind an editor’s desk, I’ve

developed a pretty good sense of what will work and what won’t. Sure, it’s

easier to separate the wheat from the chaff when it comes to other writer’s

ideas, but once I get past the initial “Eureka!” thrill moment of the birth of any idea, I can usually spot it for the

dog it is.

Likewise, I know a good one

when it comes my way. The way you

know if an idea has any legs is that when you sit down to develop it, it will

almost (as we say) “write itself.” Characters come to life, you can hear their “voices” in your head, and situations and stories suggest themselves almost as

fast as you can write them down.

So it was with Digger Graves, Paranormal P.I. As I

recounted in an earlier post, the bare bones concept--“Son of Dr.

Graves, supernatural investigator”--popped into my head during a Facebook

Messenger chat with Roger McKenzie, and came to life in a subsequent work session that lead straight into the first script, “’I’ of the Beholder!” which

was handed off to artist Andrew Mitchell to bring to life.

And, man, did he ever! The

East Village of Digger’s reality is a world full of the demonic, the damned,

and the dead, and Andy captured the casually weird and spooky ambience I had

pictured in my mind’s eye while I was writing the script. Last time around, I

posted Andy’s preliminary sketch for the first page of the story, re-presented

here for the sake of comparison...

...With the near-finished

art...

...Which is followed by

final art, with Mort Todd’s lettering laid in...

...And, the fabulous

finished page, colored by the talented Matt Webb...

And there you have it...how an idea makes its way from a spark to a comic book story. But this isn't the end of "Digger" Graves. The next story has already sparked in my brain, just waiting for me to get it on paper so we can start the whole process over again.

© Paul Kupperberg / Art ©

Andrew Mitchell