By Mark Shainblum

If you told me a year ago

that I'd be writing a new science fiction series* for Charlton Comics, I'd have

started looking around for evidence that I'd slipped into a parallel universe.

After all, Charlton Comics stopped publishing... how do we put this into proper

cultural perspective?... about a year after Scarlett Johanson was born in 1984,

three years before Emma Stone's birth in 1988, and almost a full decade before

Justin Bieber first graced the world in 1994.

Charlton Comics

evokes different responses in different people. To me, growing up in suburban Montreal in the

mid-1970's, Charlton was the oddball, Brand-X option on the "Hey Kids,

Comics!" spinner rack. It was neither Marvel-fish nor DC-fowl, and I’d

never know from month to month whether Charlton titles would even show up at

Mackle Handy Store, the closest approximation of a comic shop you were likely

to find in 1975. Charlton's comics were undeniably weird, printed on

paper that felt funny under my fingers (the covers in particular were kind of

rough and grainy) with colouring that was (to be charitable), muddy, leaning

heavily towards shades of orange and brown previously unknown to science.

Now, some of my Neo colleagues are true-blue Charlton fans, collectors, obsessives, even veteran writers or artists, but that's not the case for me. My approach to Charlton Comics then was pretty much the same as my approach to cookies, detergent and software now: I've always had a weakness for the oddballs, the off-brands, the weird stuff on the bottom shelf that no one else notices. That's why I always bought some Charlton titles mixed in with my usual allotment of Justice League, Avengers, Batman, and Spider-Man. Even though their ink smelled funny and their covers were gritty and they had no superheroes, to me Charlton represented a breath of fresh air. Even then, as superhero-mad as only a 13-year old can be, it was refreshing to have a change of pace, something different, a logo that didn't say "Marvel" or "DC" on the upper left-hand corner of the cover.

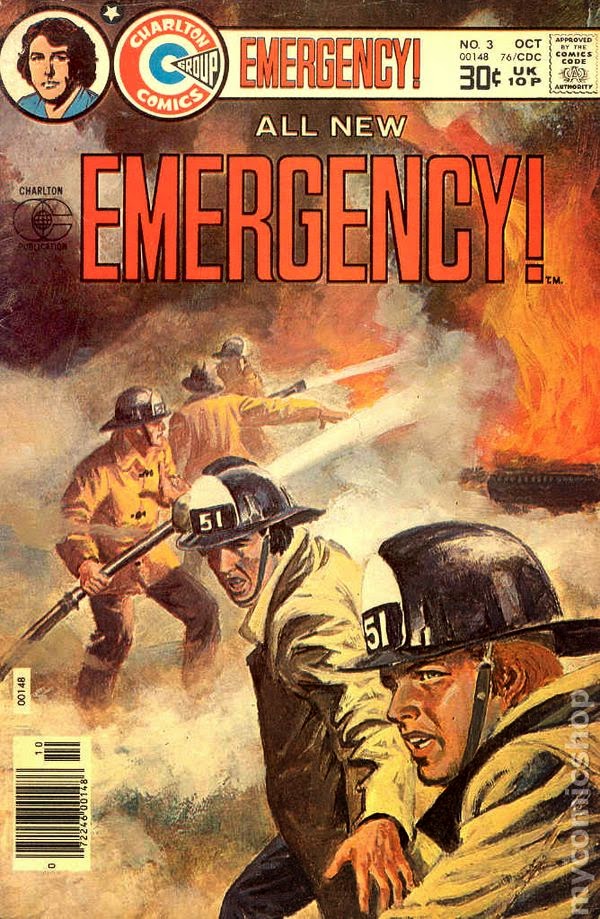

By then Charlton was already well-past its late 1960's heyday, and had largely given up on producing anything based on original, in-house properties. A few years earlier they surprised everyone by popping out an E-Man here and a Doomsday +1 there, but even that brief resurgence was over by the time I was a really confirmed comic book fan. Billy the Kid and some of the horror titles continued to stagger along, but to readers of my generation, Charlton Comics pretty much began and ended with licensed TV tie-ins: The Six Million Dollar Man, The Bionic Woman, Emergency, Space: 1999, plus one or two other titles I can't remember anymore. (Yes, it was a pretty bleak landscape when two superhuman cyborgs from TV represented an "alternative" to superheroes, but in 1975 you took what you could get.)

Charlton also

represented something very important to anyone with aspirations of one day

writing or drawing comics: It was the triple A farm team, somehow less intimidating

and more approachable than the major league bullpens at Marvel and DC. When DC

and Marvel gave up on virtually every genre except superheroes, Charlton still

had a smattering of horror, war, and Western titles. When DC and Marvel largely

abandoned anthologies and short backup stories, Charlton was still doing them;

so people like me could imagine one day breaking into the field by writing a

six-page horror or war story. How much more likely was that than being handed a

book-length Green Lantern or Spider-Man assignment for your first

try? In fact, for at least a couple of comic book generations, doing your

obligatory stint at Charlton was pretty much the only way to demonstrate that

you had the chops to work for the "big league" publishers. That's how

greats like Jim Aparo, John Byrne, Dick Giordano, Joe Staton, Mike Zeck, Steve

Skeates, Paul Kupperberg and Nicola Cuti got their starts. I could go on and on.

I missed the end of that era by a whisker. By the time I was writing professionally, Charlton was on its last legs, and I broke into the field the 1980's way, in my own self-published black-and-white comic, Northguard. I later went on to write for a bunch of other publishers; First Comics, Caliber Comics, Renegade Press, Tru Studios, and Broadway Comics among them, and they were all (well, mostly all) great. But as I got older, I couldn't help feeling that I'd missed something with the disappearance of Charlton, that I'd skipped an important step in my professional development. That wasn't entirely rational, of course, but it was how I felt.

I missed the end of that era by a whisker. By the time I was writing professionally, Charlton was on its last legs, and I broke into the field the 1980's way, in my own self-published black-and-white comic, Northguard. I later went on to write for a bunch of other publishers; First Comics, Caliber Comics, Renegade Press, Tru Studios, and Broadway Comics among them, and they were all (well, mostly all) great. But as I got older, I couldn't help feeling that I'd missed something with the disappearance of Charlton, that I'd skipped an important step in my professional development. That wasn't entirely rational, of course, but it was how I felt.

Don't get me

wrong, I have no illusions about the original Charlton. The company's origins

were shady (the founders met in prison, for God's sake!), and they were

notorious from the beginning for paying their creators bargain-basement,

lower-than-living-wage page rates, while expecting (and, surprisingly, usually

getting) first-class work. They may have had a hands-off editorial approach

that encouraged creativity and diversity, but they were also known in the field

as followers, not leaders, with a "throw everything at the wall and see

what sticks" editorial approach. It's for that reason that editorial

director Dick Giordano reportedly finally left Charlton for the greener

pastures of DC, sometime after the collapse of his great "Action

Heroes" experiment in the late 1960's.

If Mort Todd, Paul Kupperberg, Roger McKenzie, and the other new secret masters of Charlton had called the undertaking something else, if they hadn't explicitly modeled the new Charlton on the best of the old Charlton's legacy – while leaving the bad parts in the dustbin of history, where they belong – I don't think this community of creators would ever have gotten off the ground, because that's what it is: Not a company in the traditional sense, but a community. We all come from different generations, from different artistic backgrounds, even from different countries, but I think it's fair to say that for most of us, Charlton Neo somehow feels right, like we're coming home.

Mark Shainblum is the co-creator of Northguard and he is

currently co-editing the prose superhero anthology Superhero Universe:

Tesseracts Nineteen from EDGE Publishing. His website is www.shainblum.com.

*More on that

later.

© Mark Shainblum

Now if only we could get a Charlton Northguard series out of you.

ReplyDeleteWell, it's actually coming from Chapterhouse Comics. Hope that's okay!

Delete